We all know that plants depend on the soil to grow and thrive, but did you know that they can modify the soil too? When you think about what a plant’s root structure looks like, you’ll get an idea why …

The soil does not, in fact, provide everything a plant needs freely, and it isn’t necessarily a welcoming environment for plant growth. We know this because plants are forced to engage in huge amounts of soil modification to improve their chances of survival. They are also included in the five soil formation factors, which are:

- Organisms (including plants)

- Climate

- Relief/topography

- Parent material

- Time.

How do plants modify the soil?

- Chemically

- Biologically

- Physically.

In this blog post, we look specifically at how plant root structures physically affect the soil.

Roots are the unseen half of the plant. Even though we don’t know all the functions they perform, we do know that a plant’s roots are its primary means for resource acquisition. We also know that they release complex chemical compounds that affect carbon-sequestering in the soil, that they influence other soil organisms, and that they leave the soil modified after an interaction.

Let’s delve deeper (get it?) into root structure

Root structure is called the architecture of the roots, which includes the roots’:

- Physical arrangement

- Number

- Thickness

- Length

- Depth

- Angles of branching

- Distribution of root orders.

Different plants have different root architectures. The general root architecture of a plant can tell you a lot about its survival strategy. When the root architecture changes, we can learn about the specific stresses it has been exposed to.

Root order

No, it’s not maths terminology, but an easy way to gain a greater understanding of root architecture.

- The largest central root = the primary or seminal root

- A root that branches off the seminal root = a first-order lateral

- A root that branches from a first-order lateral root = a second-order lateral.

And so on … until the small roots begin to produce fine root hairs.

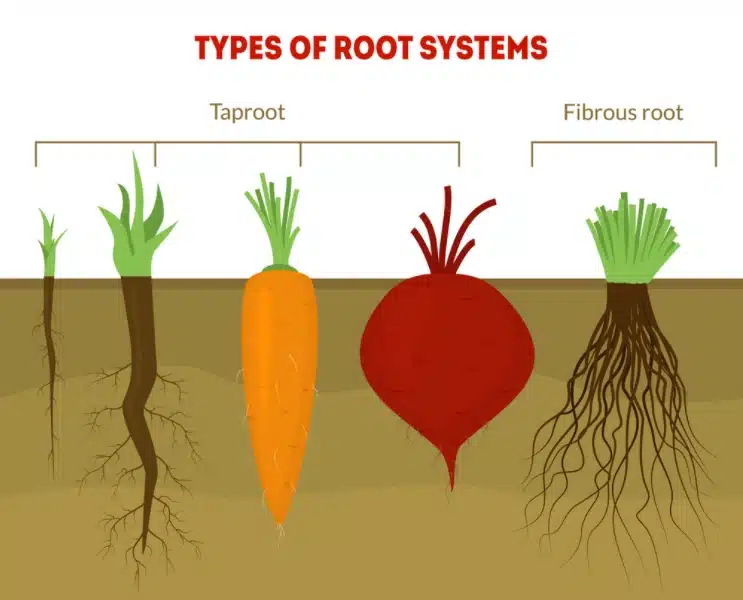

The two basic types of root systems

- Taproot system: dominant and easily-recognisable downward growing single root from which all the other roots branch out.

- Fibrous root system: a root system with many more seminal roots and often no clear primary root.

This is, of course, a simplification, and there is a much greater variety in architecture. For the purposes of showing how different root structures affect the soil, however, we will focus on these two main architectures.

What does each type tell us about the plant and the soil?

- Taproot system: the plant’s survival strategy relies on access to water nutrients held deeper in the soil.

- Fibrous root system: the plant’s survival strategy explores closer to the surface, with high contact with soil particles to acquire nutrients without having to reach too deep down.

These two main types of roots systems thus modify the soil in different ways due to the different distributions of physical disturbances in the soil. These include voids, macro channels, and aggregate formed from decomposing tissue and roots. The modifications caused by the root structure also affect the soil’s water infiltration and retention properties.

But the structure of the soil and the plant do not work in isolation. For a plant’s root architecture to be able to proliferate, it needs a soil with good tilth (properties that promote plant growth, such as well-developed aggregates and macroporosity). In turn, a plant’s root architecture helps to maintain proper tilth.

Healthy root structures start in the soil

At Zylem, we aim to create an optimal balance between soil health and plant health, through programmes utilising a combination of our own biological soil conditioners with microbial products and other soil food.

Get in touch to find out more about our soil health solutions. Contact us on 033 347 2893 or send your enquiry to admin@zylemsa.co.za.

About the Author: Alex Platt

Alex is Business Development Manager at Zylem. He’s inspired by the potential of regenerative farming and takes a special interest in the technology and products that are moving agriculture in a more sustainable direction.